David Koresh, Adventism, and the Deadly Cost of Prophetic Error

By ,

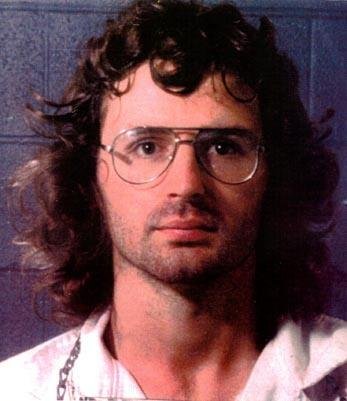

The 1993 siege of the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas remains one of the most disturbing religious tragedies in modern American history. At its center stood David Koresh, a self-proclaimed prophet whose apocalyptic certainty ultimately led to the deaths of more than seventy men, women, and children. While Koresh is often portrayed as an isolated fanatic, his theology did not arise in a vacuum. His worldview was shaped decisively by Seventh-day Adventist [SDA] prophetic traditions inherited from Ellen G. White.1

Understanding Koresh requires more than psychological speculation. It requires examining the theological ecosystem that convinced him – and those who followed him – that they were living at the very climax of biblical history. The Waco tragedy stands as a sobering warning of what can occur when speculative prophecy is elevated to unquestionable truth.

Seventh-day Adventist Roots

David Koresh was born Vernon Wayne Howell in 1959 and was raised within the Seventh-day Adventist Church. As a young man, he immersed himself in SDA teachings, particularly its historicist interpretation of Daniel and Revelation. Scholars have long noted that the Branch Davidians were not an aberration but an offshoot of Seventh-day Adventism itself, inheriting its Sabbath observance, prophetic charts, and end-time expectations.2

The Branch Davidians traced their lineage through Victor Houteff, an SDA reformer who claimed special insight into prophecy during the 1930s. Houteff’s teachings, though rejected by the SDA denomination, retained Seventh-day Adventism’s core apocalyptic framework. Koresh would later radicalize this framework, placing himself at the center of biblical fulfillment.3

The Influence of Ellen G. White

Central to SDA prophetic thought is the authority of Ellen G. White, whose writings interpret world events through an apocalyptic lens. Mrs. White repeatedly warned of an approaching final crisis in which faithful believers would be persecuted by civil authorities. This narrative of inevitable confrontation shaped SDA self-identity and profoundly influenced later splinter groups.4

Koresh adopted this persecution framework wholesale. He interpreted opposition not as correction but as confirmation. Government scrutiny became proof that prophecy was unfolding precisely as expected. This hermeneutic rendered dialogue impossible, as any challenge was reclassified as satanic opposition.

The Seven Seals and Prophetic Absolutism

Koresh’s defining claim was his exclusive ability to interpret the Seven Seals of Revelation. He taught that the meaning of Scripture had been sealed until his arrival, effectively positioning himself as the final prophetic authority. This mirrors a recurring pattern within Adventist history, where reinterpretations of failed prophecy are preserved through claims of deeper insight rather than abandoned.5

By identifying himself as the Lamb who could open the seals, Koresh removed all external checks on his authority. Scripture no longer judged the prophet; the prophet judged Scripture.

Apocalyptic Siege Mentality

As federal authorities investigated allegations of weapons violations and abuse, Koresh interpreted every development through an apocalyptic filter. Law enforcement officers were not neutral agents of the state but actors in an end-time drama. Negotiation was impossible because surrender would have meant theological defeat.6

Sociologists of religion have repeatedly observed that apocalyptic movements become most dangerous when prophecy and self-preservation collide. Waco exemplifies this tragic convergence.

The Catastrophic End

On April 19, 1993, the siege ended in fire. Whether intentionally set or ignited amid chaos, the result was catastrophic. Entire families perished, convinced to the very end that obedience to Koresh was obedience to God. The outcome stands as a grim testament to the destructive power of prophetic certainty divorced from biblical restraint.7

A Sobering Moral Lesson

The lesson of Waco warns us of the danger of trying to self-identify one's organization with the symbols of Revelation. When Bible prophecy is treated as a closed system immune to correction, it ceases to instruct and begins to dominate. The tragedy of David Koresh illustrates how misinterpreted prophecy can deform conscience, justify cruelty, and sanctify destruction.8

True biblical prophecy humbles the interpreter. False prophecy enthrones him.

Citations

- Newport, Kenneth G. C., The Branch Davidians of Waco (Oxford University Press, 2006).

- Seventh-day Adventist Encyclopedia, rev. ed., entry: "Branch Davidians."

- Hall, John R., Gone from the Promised Land (Transaction Publishers, 1987).

- White, Ellen G., The Great Controversy (1911).

- Tabor, James D. and Gallagher, Eugene V., Why Waco? (University of California Press, 1995).

- U.S. Department of Justice, Report to the Deputy Attorney General on the Events at Waco (1993).

- Reavis, Dick, The Ashes of Waco (Simon & Schuster, 1995).

- Wessinger, Catherine, How the Millennium Comes Violently (Seven Bridges Press, 2000).